Poverty Porn: The Feel-Good Genre That Lets Us Stay the Same

Why you’ve been sucked in by the ads, the fundraisers, the reality TV and influencers - and what does it say about us as a society?

Welcome to my last themed post of the year! We made it. Thank you for being here and joining me on this journey to dissect our relationship with money and all the aspects of life it touches. I’ll eventually run out of things to talk about (just kidding, I could do this forever), but I’d love to hear your requests on topics you’d like me to cover and discuss - please get in touch, or comment below!

I have exciting things planned for this community in the new year - so watch this space for updates!

Reminder: our final Finance Therapy Circle of the year is tomorrow, 18th December, 5.30pm. Join us as we reflect on the year past and think about how we’d like our relationship to money to evolve in the year to come!

Fearless Funding School applications are open and the early bird offer is still on, so grab your slot on our cohort kicking off 29th January 2025. Applications will close in mid Jan, so secure your seat ASAP! I’d love it if you could share this with any funders, investors, grant makers, VCs, Private Equity humans in your network.

Let’s get into it!

Tis the season: of giving, to be jolly and to cry at John Lewis adverts - not a single advert has made me cry this year, even through a luteal phase - I guess replacing with staff with AI hasn’t quite panned out & it shows cough Spotify wrapped cough Speaking of, here’s our year wrapped:

Another huge thank you for being a part of this journey so far! Your views are what kept me going (ironic, given what you are about to read).

Did anyone see Amazon’s pathetic attempt at evoking emotion in their Christmas ad? Something about a company that’s globally renowned for its poor treatment of warehouse workers, using a janitor being gifted a dinner jacket and transformed into a Frank Sinatre-esque singer performing “What the world needs now” that’s rubbing me up the wrong way. By all means, rebrand away - just try singing from your own hymn sheet next time!

Also, what’s with every sh*tty Christmas movie (which is a staple ‘its cold and dark outside’ activity), being about some marketing exec trying to save someone’s failing family business, with a woven in love story and some version of helping out at the local shelter? - Calling on Hallmark to bring back Mrs. Miracle!

As Christmas approaches, we’re surrounded by messages encouraging us to give back: heartstring-tugging charity ads, viral videos of influencers helping strangers, and holiday-themed reality TV specials. It’s the season for generosity, for reflecting on our good fortune, and for supporting those less fortunate. But how much of this festive giving is driven by genuine empathy, and how much by the pull of what I like to call “poverty porn”?

Relax, it’s not what you’re thinking

Poverty porn refers to media and content that depicts the hardships of disadvantaged people in a way designed to elicit an emotional response from the viewer, often without addressing the root causes of the issues it portrays. Think shows like Rich House, Poor House, where affluent families trade lives with struggling households for a week and then meet up to dissect their experience - aka rich people learnt that life is hard as a ‘Povvo’ - duh. Or Undercover Boss, where CEOs don disguises to “see” how their employees work and live, culminating in grand gestures of benevolence. These programs thrive on stark contrasts and emotional resolutions, creating compelling entertainment that highlights suffering but often stops short of inspiring systemic change.

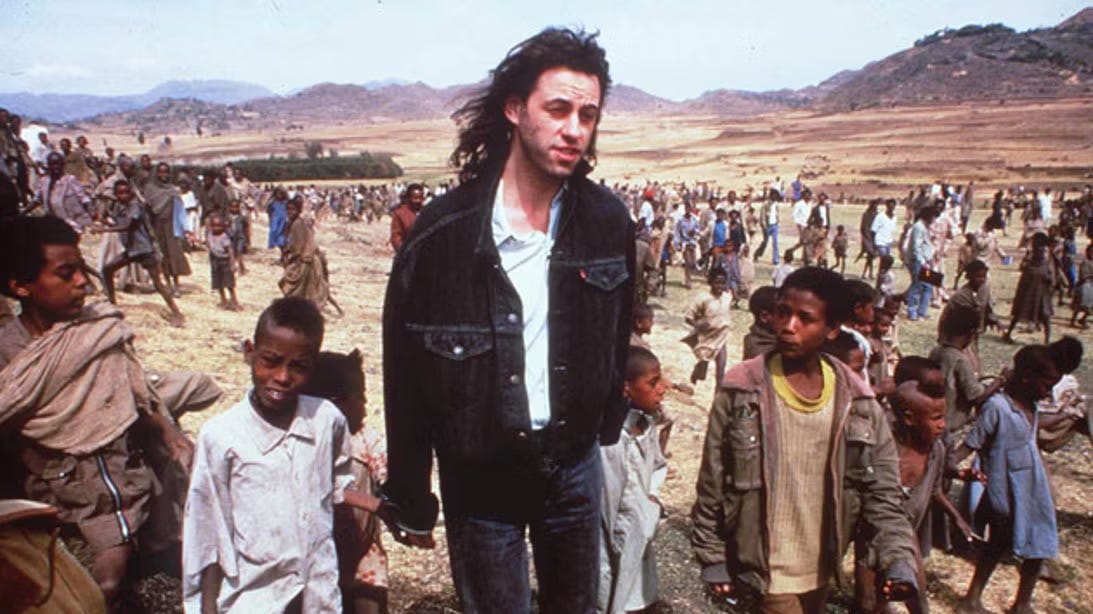

Charity campaigns and holiday fundraising appeals lean heavily into similar strategies, relying on images of hungry children, barren lands, dilapidated homes, and tearful testimonials. The imagery and narratives evoke a sense of urgency and guilt in viewers, encouraging donations to “help those in need.” While these campaigns raise significant funds, they also perpetuate simplistic and often harmful stereotypes about poverty - especially in so-called “third-world” countries.

The Festive Formula for Giving

The festive season amplifies this emotional appeal. Advertisements like those from UK retailers or global charities ramp up the tug-at-the-heartstrings effect. They use sweeping music, stories of triumph over adversity, and imagery that’s just bleak enough to move us to open our wallets. Campaigns like Band Aid’s “Feed the World” and older Live Aid initiatives, though well-intentioned, position entire regions as helpless and dependent on Western goodwill. These narratives reduce complex socio-economic and political realities to digestible, feel-good binaries: us as saviours, them as beneficiaries.

I can’t be the only one who grew up questioning the lyrics “Do they know it’s Christmas time at all“. It turns out I’m not, people of colour have found their voice and it sounds like a resounding “the song is patronising, redundant and unoriginal” and that it "reeks of the white saviour complex because it negates local efforts that have come before it" - Robtel Pailey, from Liberia and student at the School of Oriental and African Studies told the BBC in 2014.

The Psychology of Poverty Porn

Morgan Housel, a sequel, perhaps?

Why do we respond so predictably? Part of it is psychological. Seeing stark inequality juxtaposed with our relative privilege triggers activity in the parts of our brain associated with emotional reasoning. It bypasses critical thinking and taps directly into our feelings of compassion and discomfort, and giving offers a quick way to alleviate that feeling. It’s why charities often use emotionally charged advertising rather than facts and figures: it works. Walking around London this winter, I’ve personally stopped to read the signs of nearly every homeless person who has expressed they have fallen on hard times, then tried to find a way I could help more than I usually would.

This emotional engagement is designed to create urgency. We want to relieve the unease we feel when confronted with stark inequality, and giving - whether it’s a donation or a share of a viral video - offers an immediate sense of resolution. Psychologists call this “compassion fade,” where focusing on individual stories is more compelling than thinking about large, systemic problems. The heart overrides the head.

Marketing and media producers are well aware of this effect. By highlighting individual suffering, they make it personal, leaving us feeling morally compelled to act in small, manageable ways. This “emotional bait” is effective, but it also fosters a shallow connection to the issues at hand, and often, our response ends there.

Influencers want in

The internet has added a new twist to the poverty porn formula. Enter influencers like Mr Beast, whose meteoric rise is tied to giving strangers things - from cash to cars to life-changing surgeries - on camera. Millions of viewers are drawn to these videos, which present acts of generosity as entertainment.

At face value, this might seem like a win-win: someone in need gets help, the creator gets views, and the audience feels good. But it raises troubling questions. Does this model turn the act of giving into a spectacle? Are recipients being used as props to build influencers’ brands? And does watching these videos lead viewers to reflect on systemic inequality - or simply leave them waiting for the next episode?

This brand of content also reflects and reinforces the “saviour” narrative. In many cases, it emphasises the giver’s generosity over the agency or dignity of the recipient. It’s philanthropy packaged as feel-good entertainment, but it rarely addresses the structures that keep people in need - which the influencers need for their content, right?

I’ve had many a dude argue that Mr Beast is a great guy who cares, and if I wasn’t sceptical before, November’s news of his alleged $20m in crypto scams certainly hasn’t given me any reassurance of his kind nature and good soul. Seems to me your many, many views got him paid and then the crypto bros and YouTube stans got played. Mo money, mo problems, indeed.

The Warm and Fuzzy Trap

So why do shows and videos like these make us feel so good? The answer lies in psychology. Watching someone “give back” activates our sense of moral satisfaction, allowing us to vicariously participate in altruism without actually having to act. It’s a powerful escape from guilt: we’re moved, we applaud, and then we carry on with our lives, comforted by the knowledge that “someone’s doing something.”

This, perhaps, is the most insidious aspect of poverty porn: it creates an emotional high that tricks us into feeling we’ve made a difference, even if our behaviours and priorities don’t change at all. We may donate in the moment, but the systemic inequalities depicted in these stories persist, as does the content cycle that exploits them.

Morality and Change

Is poverty porn morally wrong? That depends on perspective. On the one hand, it undeniably raises awareness and funds that can help people in immediate ways. On the other, it risks commodifying suffering and reducing individuals’ lives to emotional story arcs for the consumption of more privileged audiences.

As viewers, it’s worth asking ourselves: why do we enjoy these shows and videos? Is it curiosity, guilt, or genuine compassion? Are we consuming this content passively, or are we using it as a starting point for action? And if we’re donating, are we also pushing for systemic changes that address poverty at its roots - changes that would make such content unnecessary in the first place?

In the US only 8% of all grants are awarded to people of colour, the very people who suffer at the hand of inequality the most. So whilst we’re on the topic of giving - isn’t it time we started paying attention to the systems that facilitate giving and who controls them in the first place? There’s no point in giving the money if you aren’t also willing to transfer the power.

Moving Beyond Feel-Good Moments

This festive season, let’s think critically about the relationship we have with poverty porn. Instead of simply responding emotionally to ads and viral videos, consider other ways to engage. Seek out organizations addressing the systemic causes of inequality, not just the symptoms. Learn about how your own habits, from shopping to investing to voting, might perpetuate or reduce inequality. And most importantly, remember that true generosity isn’t about what makes us feel warm and fuzzy but about what creates meaningful, lasting change.

Poverty porn might entertain and inspire, but it can’t solve poverty. That part is up to us.